Product First Stories: <Eval>

Product First Stories: <Eval>

Revolutionizing the Barrier Market

Kuraray was first in the world to develop and commercialize a high-barrier performance

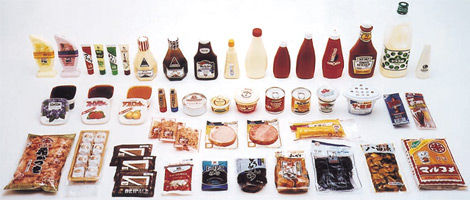

resin – EVAL. Development began in 1957 with the aim of improving PVA resin, and took fifteen long years from the start of serious basic research. This resin has the highest gas impermeability of any plastic (against gases such as oxygen) and prevents the deterioration of whatever it contains. EVAL has been a market success, with numerous applications such as in containers for mayonnaise and ketchup or in food packaging for flaked fish and soy bean paste, to name just a few. An even broader range of applications for this resin are being developed, including for use in artificial kidneys and in fuel tanks for automobiles. EVAL resin has become essential for modern living.

The Reformulation of PVA as the Starting Point

Supermarkets began to proliferate rapidly across Japan in the late 1950s, driven by economic growth. While plastic materials such as polyethylene and vinyl chloride were gaining attention, need grew for a food packaging material that was light-weight and capable of preserving foods longer. Against this background, in 1957 Kuraray launched a full-fledged research project focused on deriving plastics from vinyl acetate1 (the raw material used to create PVA).

In order to make a plastic resin through the reformulation of (modifying) PVA, it was first necessary to reduce the hydrophilic characteristics of the material, which is its best property. Based on efforts involving the copolymerization2 of various kinds of monomers,3 the R&D team found that only ethylene produced the desired result. The crystalline structure of most of the polymers would break down during copolymerization depending on the monomer selected and the resulting polymer would become useless as a plastic. The exception was ethylene, which was a rare type of polymer that retained its crystalline structure.

At the time, it was not clear if ethylene copolymers could be used as plastics because they were not easy to handle and were expensive. However, the research team made a major breakthrough, partly by chance – it was the discovery of the excellent gas barrier properties of the material. Although the gas barrier properties of PVA degraded as humidity rose, the hydrophilic nature of PVA was suppressed if it was copolymerized with ethylene. This made it possible for the material to retain excellent gas barrier properties under normal humidity conditions, something that had not been possible before. This was the moment when EVOH (ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer) was born. This high-performance resin later came to be called EVAL.

Hurdles to Commercialization

Kuraray began a joint development project with a major food processing company to commercialize EVOH in 1964. The first difficultly Kuraray encountered was determining the extent of gas permeability with sufficient precision. The first trials to evaluate permeability consisted of checking the surface color of miso (soy bean paste) wrapped in a bag made with EVOH film, then measuring the oxygen concentrations in a bag filled with nitrogen. The precision of these evaluation methods had its limitations. For this reason, Kuraray painstakingly developed a hand-made glass measuring device in cooperation with a university study group and then spent about two years measuring permeability. As a result, Kuraray was able to demonstrate the excellent gas barrier properties of EVOH film. Kuraray submitted a basic patent application for food packaging based on the test results in March 1966 and made preparations to begin commercializing EVOH. The discoveries made during this process were to play an important role for years to come.

Despite receiving the patent, serious disputes continued among management for years about whether or not to go ahead with R&D into mass production technology, because a huge investment was required. Although at first there were 30 members of the R&D team engaged in the development of mass production technologies, the number of researchers was drastically reduced. At one point, things reached such an extreme that there were only two researchers assigned to work on the film application aspect of development.

Under such circumstances, President Soichiro Ohara issued a statement in 1967 that said “It is easy to cancel a project, but if we think about the corporate system of the future, cancellation can wait one more year. Consider it deeply.”

This encouraged the R&D team. In 1968, only twelve months later, the prospects for commercializing EVOH were successfully determined, and a full-scale test plant was completed for production of 200 kilograms per day in 1969. The name EVAL was also given to the product at this time. In the end, it took fifteen long years from the start of basic research and accumulation of knowledge by the R&D team to when EVAL was commercialized in 1972.

Two Strokes of Good Luck

EVAL garnered a lot of attention as a food packaging material with great potential when it was first introduced, especially as its appearance coincided with the dawn of the plastics era. In addition to excellent gas barrier properties, it was extremely safe because it did not contain any additives, such as plasticizers or stabilizers, which also contributed to it being highly regarded as environmentally friendly. Expectations for EVAL grew even more because it was better suited to food packaging than conventional materials such as plastic bottles or jars.

The market for EVAL developed very quickly as it came to be used in an ever-widening range of applications through the combination with polyethylene or polypropylene. Applications included use as packaging film for preserved foods such as katsuokezuribushi (flaked bonito fish used in Japanese cooking) and miso (soy bean paste), use as food containers for mayonnaise, ketchup, soy sauce and other types of sauces and edible oils, as well as use in pharmaceutical containers. EVAL also entered the medical market through its successful use in the development of artificial kidneys using hollow-fiber membranes.4

There were two strokes of good luck behind this success story. One concerned the thermoforming technology that enabled EVAL to be melted and extruded at temperatures ranging from 200℃ to 220℃. Although the melting point5 of PVA resin is around 240℃, which is close to the point where thermal decomposition of the material occurs, a less expensive method for extrusion of EVAL could be used because its melting point was approximately 60℃ lower than its thermal decomposition point. This proved to be a significant merit of EVAL.

The other stroke of good luck was the development of a technical innovation known as coextrusion technology.6 Normally, film laminate processing was necessary, but coextrusion techniques made it possible to avoid such processing. Many applications of EVAL became possible as a result of this technology, and the demand for EVAL increased tremendously.

EVAL Goes Global

EVAL grew to become a major source of revenue for Kuraray. It also played a leading role in the globalization of the company.

When full-scale exports of EVAL to the U.S. began in in 1982, the name EVAL was already well known from coast to coast and demand quickly grew. This led to the founding of EVAL Company of America (EVALCA) as a joint venture with Northern Petrochemical Company. The new company soon assumed local production of EVAL in 1983. EVALCA began to produce EVAL in Houston, Texas in December 1986. It was decided that the plant should have an initial capacity of 10,000 tons per year based on estimates for a high-growth rate, even though total annual sales of EVAL at the time were only 1,000 tons.

This decision brought about a revolution in the large market for food containers in the United States. A similar strategy was adopted in the European market, but with a different timetable. Thus, a global framework consisting of Japan, the U.S., and Europe was established. This further enhanced Kuraray’s ability to respond flexibly to market needs.

The history of the evolution of EVAL also mirrors the history of growing concern for the environment. Each time an environmental issue arose somewhere in the world, whether it was the PVC7 residue monomer problem that occurred in Japan in 1973, the movement to replace PVDC8 and PVC as a result of problems associated with acid rain in Europe in 1980, the revision of the Clean Air Act in the U.S. in 1990, or the introduction of the California Air Resources Board (CARB) Regulations in 1995 also in the U.S., EVAL made significant contributions to helping to resolve these problems through its use as an alternative material.

In particular, the development of plastic fuel tanks (PFTs) for automobiles, which began in 1992, demonstrated the excellent gas barrier properties of the material by preventing the evaporation of gasoline from the tank, while at the same time helping to reduce automobile weight. Two years later, PFTs were commercialized in the U.S., and succeeded thereafter to develop into a new large-scale market.

Kuraray has been pushing ahead with a basic business strategy of promoting EVAL; that is, manufacturing it where it is suitable to manufacture it and selling it where it is suitable to sell it. For example, U.S. production capacity was increased in 1997 to accommodate the strong market demand for barrier products including PFTs, and European production facilities were upgraded in 2004 to address environmental concerns.

There is an unlimited range of needs in the global market for barriers of various types beyond those used to prevent the leakage of gas and evaporation of fuel, including barriers for scents or aromas, heat, dirt or grime, as well as light rays. Kuraray is dedicated to providing the most advanced technology available to meet the ever-growing demand for barrier-type products and to playing a leading role in the global barrier material market with EVAL.

- Vinyl acetate is an organic compound with the formula CH3CO2CH=CH2. By converting vinyl acetate into a resin, it can be used in such applications as PVA fiber, adhesives, laundry starch, artificial lawn material, wood glue, and chewing gum ingredients.

- Monomers are simple compounds whose molecules can combine to form polymers. While macromolecules are called polymers (poly means many), monomers consist of one molecule (mono means one) only.

- Polymerization refers to any process in which two or more types of monomer are combined chemically to produce a polymer, without changing the basic structure (atomic arrangement) of the base materials. Copolymerization is a process in which more than one monomer is used to produce a copolymer.

- A fiber with a space in the center like a micro tube. It is used for textile materials and as a filter to prevent impurities from passing through the fiber.

- Melting point is the temperature at which a solid substance starts to melt into a liquid.

- Coextrusion is a film processing method used to extrude two or more materials through a single die with two or more openings arranged so that the extrudates merge and fuse together into a laminar structure in a state of fusion.

- PVC: Polyvinyl chloride.

- PVDC: Polyvinylidene chloride.

(2006)